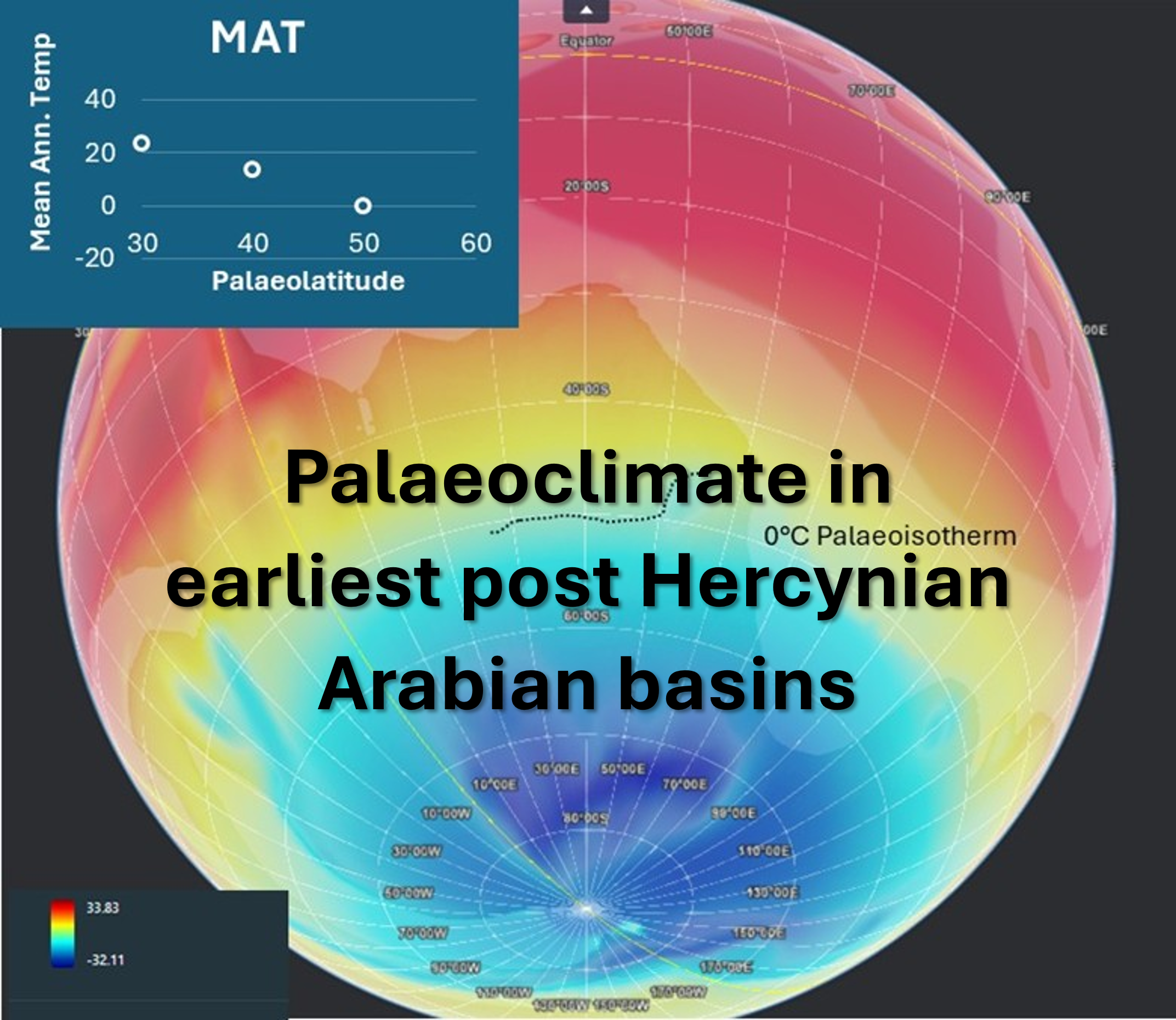

Palaeoclimate in earliest post Hercynian Arabian basins

How did palaeoclimate vary across the Arabian region in basins following Hercynian tectonism – and how did this affect sedimentary facies and therefore petroleum potential? Recent palaeotemperature and palaeoprecipitation modelling (Li et al., 2022) as part of the Earth Explorer Deep-time Digital Earth tool, allows some of these questions to be answered. Modelling indicates the palaeogeographic limits of glacially-influenced sedimentation in the earliest post Hercynian (the oldest Unayzah, Al Khlata and Akbarah units), and shows a very steep palaeotemperature gradient north to south in the region, which no doubt had a strong influence on facies.

Key Hercynian palynomorphs

This short article and accompanying diagram summarises the key palynological taxa associated with the Carboniferous and Permian beds above and below the HU across the Arabian Plate. Since the HU is mainly a subsurface feature, the basic stratigraphic data comes from key wells in the public domain that span the subcontinent in both basinal and basin margin positions, and public domain wells that contain core-based palynological information that covers the pre- and post HU. However, information on a few key outcrops is also used.

Online, on demand, CCS training

This new course presented entirely online, on demand, covers carbon capture, utilisation and storage.

It’s delivered through the world class platform of Wray Castle with its team of highly experienced specialist course developers and instructors that come with decades of experience from within industry and as specialist technical trainers.

The course satisfies a part of the market that is not currently catered for – the wider science, risks, financing, planning and social licence aspects of CCS. These are issues that are as important as the technical issues (in, for example, reservoir engineering) in the sense that any of these elements can be a show-stopper for CCS. Although the course will cover the technical geological and engineering aspects of CCS, it will also consider how these technical, policy and science aspects affect planning, regulation and financing of CCS. There are geologists, planners, investors and policy makers in companies, government natural resource and planning departments, investment banks and among NGOs that require this information from an unbiassed technically well informed and up to date source. This course provides that source.

Bridge species

The Permian is one of the most palaeophytographically differentiated periods in the Phanerozoic (Stephenson 2016) with the result that it is sometimes difficult to correlate across and between Permian continents. This is a particular problem between Gondwana and Euramerica in the Cisuralian because the GSSPs of the Cisuralian are not Gondwanan, and because the two regions were very different in the Permian phytogeographically and faunally. This means that ‘bridge taxa’ or ‘bridge species’ that occur between or throughout distinct Permian palynological provinces become very important because they can allow cross-province stratigraphic correlation.

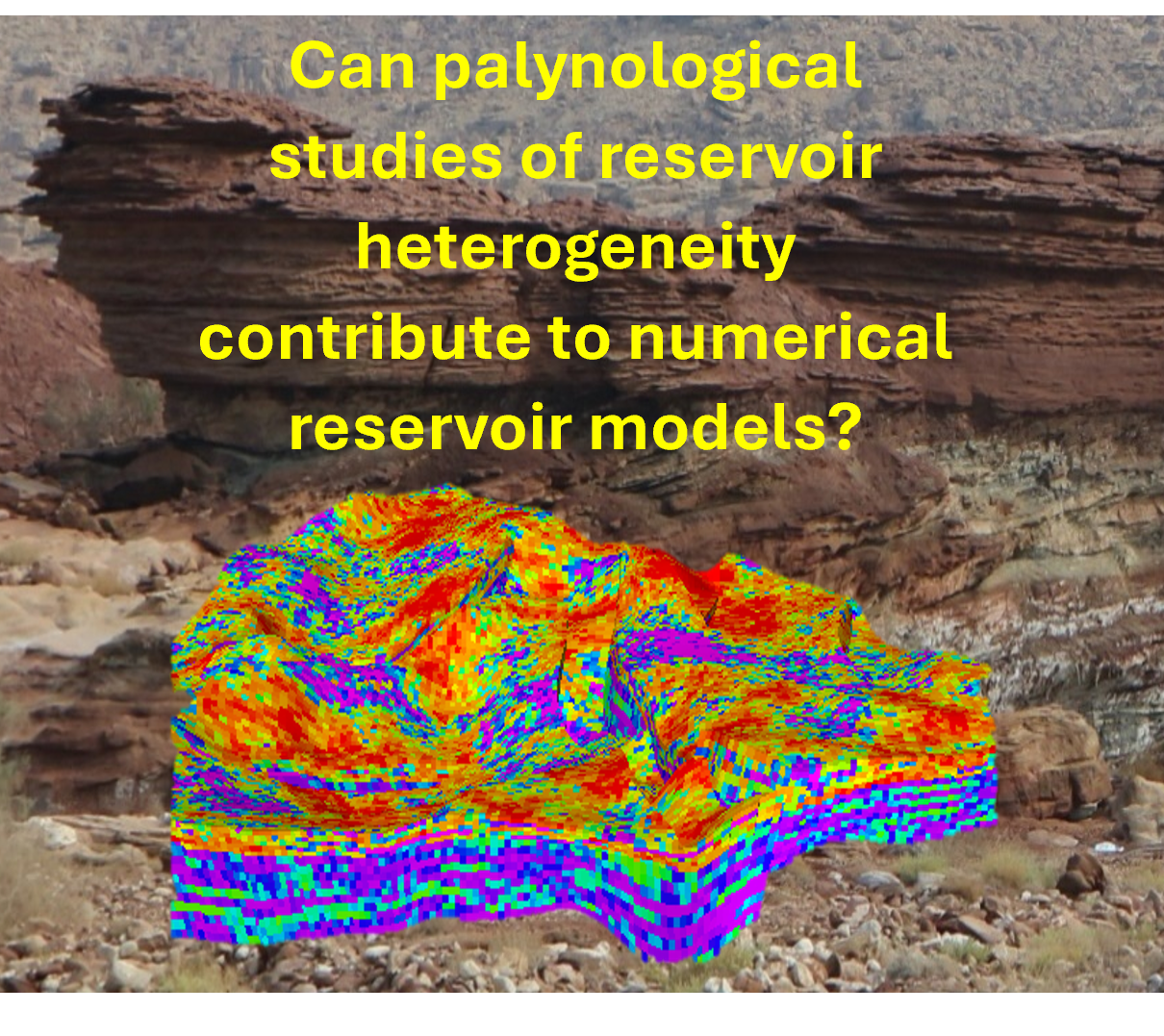

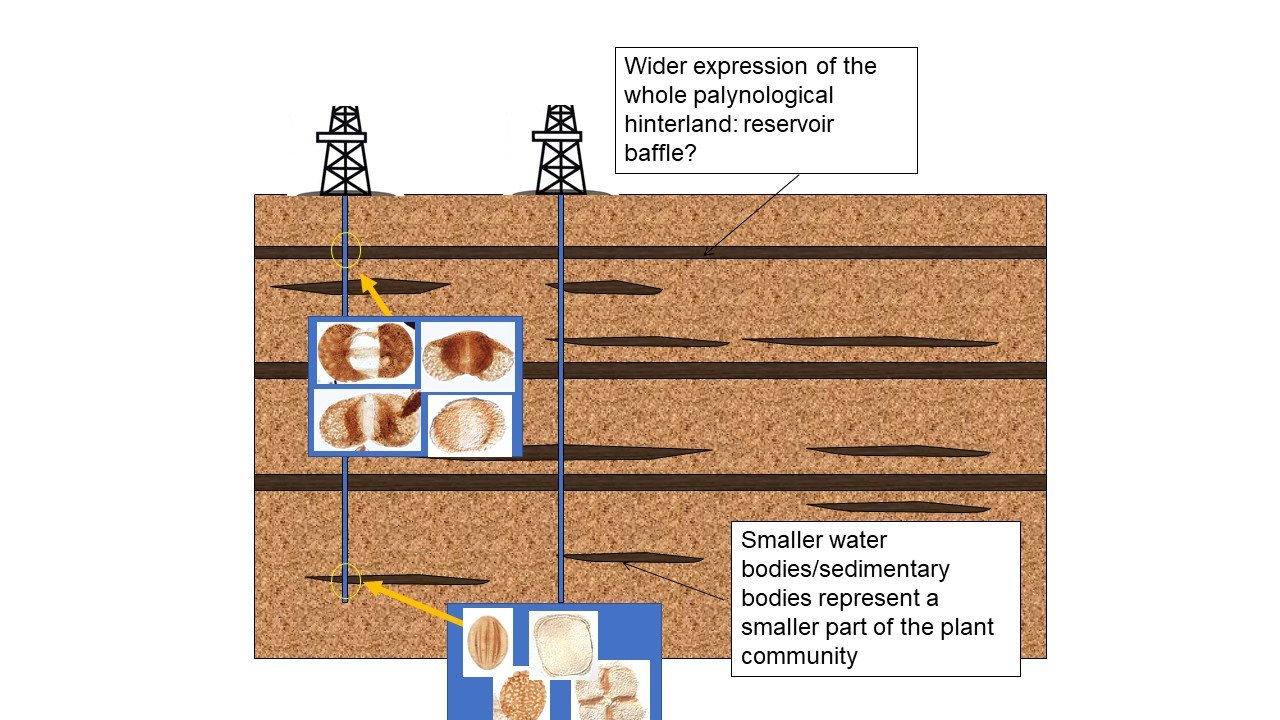

Palynology and reservoir models

This recent paper discussed the lateral and vertical variation in palynology within individual argillaceous units, as well as lateral variation between different argillaceous units in the same sedimentary complex at similar stratigraphic levels. It aims at a tool for understanding more about why mudstone heterogeneity happens and ways of predicting heterogeneity in the subsurface. In this new article, I look at ways that this initial published work could be extended as part of a reservoir model workflow, by statistically assigning levels of likelihood that mudstone units could act as reservoir baffles.

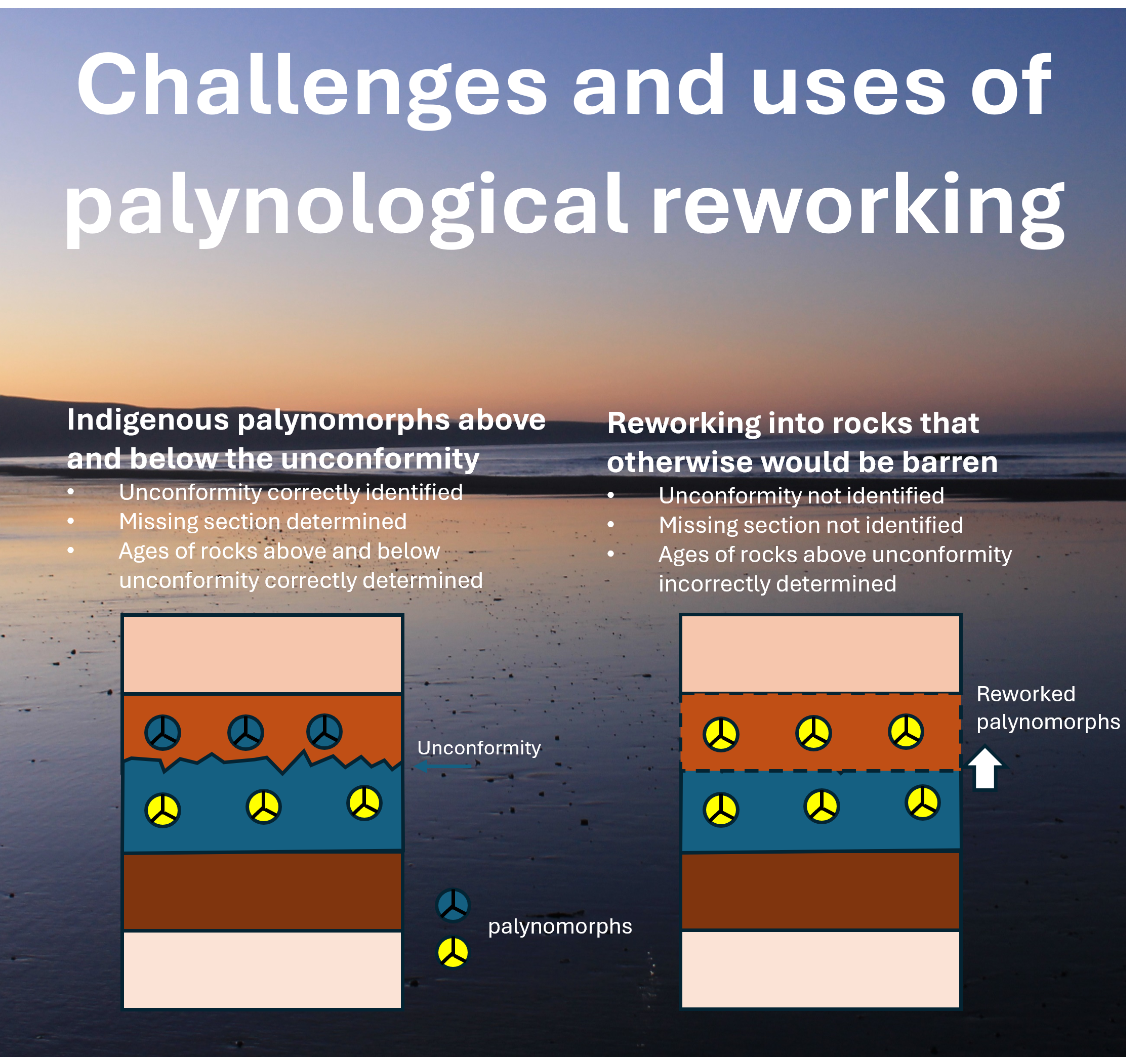

Challenges and uses of palynological reworking

Palynomorphs are of a similar size to silt particles, and being relatively tough and durable, are capable of being eroded from unconsolidated sediments or solid sedimentary rocks (like silt sized clastic particles) and then included into younger rocks deposited above. In the early days of palynology, this kind of reworking was considered a hindrance to dating and correlation because it was often difficult to tell between reworked and indigenous (i.e. in situ) palynomorphs. However more modern studies have shown the uses of reworking. In this short article I review some of the problems that reworking causes for stratigraphers and geologists, consider some of the uses of reworked palynomorphs helping geologists to understand basin history, and look forward to useful research on reworking .

AI in palynological taxonomy

Artificial Intelligence is becoming an interesting avenue of research in geology. Recently the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) Deep-time Digital Earth (DDE) team, and partners Alibaba Cloud, have begun to develop a large language model for geology known as GeoGPT. The team also wanted to know if large language model methods could augment a traditional taxonomic key. Could a palynologist sitting by their microscope get some help from a Large Language Model (LLM) in determining a species?

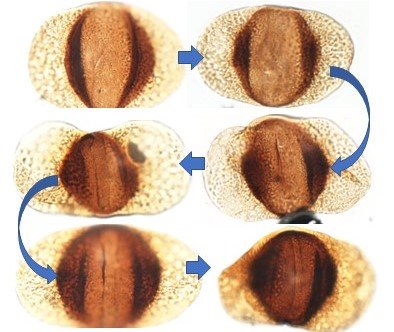

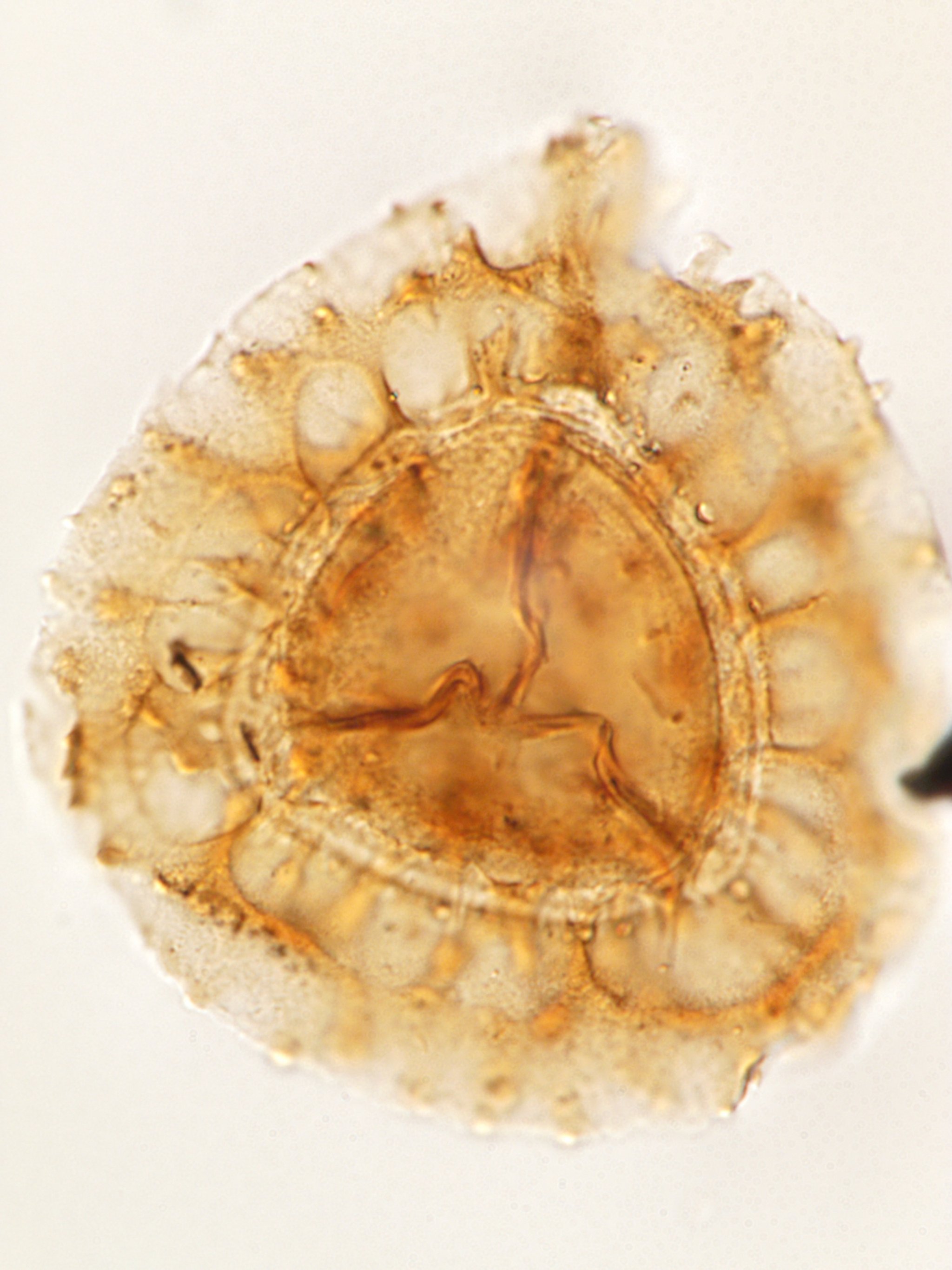

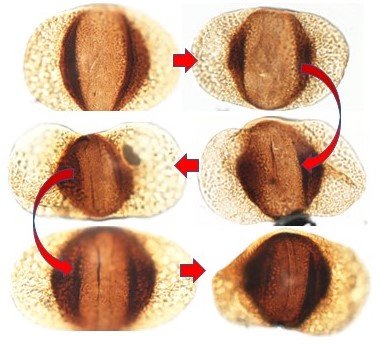

Spore structure

The study of zonate-camerate spores through Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) has led to a better understanding of their internal structure and affinities. However TEM is expensive, time consuming, involves concentration on a small number of specimens, and is often inconsistent with practical palynological study which is still overwhelmingly carried out by light microscopy. In this article I show that light microscopy of well-preserved - and particularly of broken specimens - can reveal much about the internal structure of specimens of Vallatisporites.

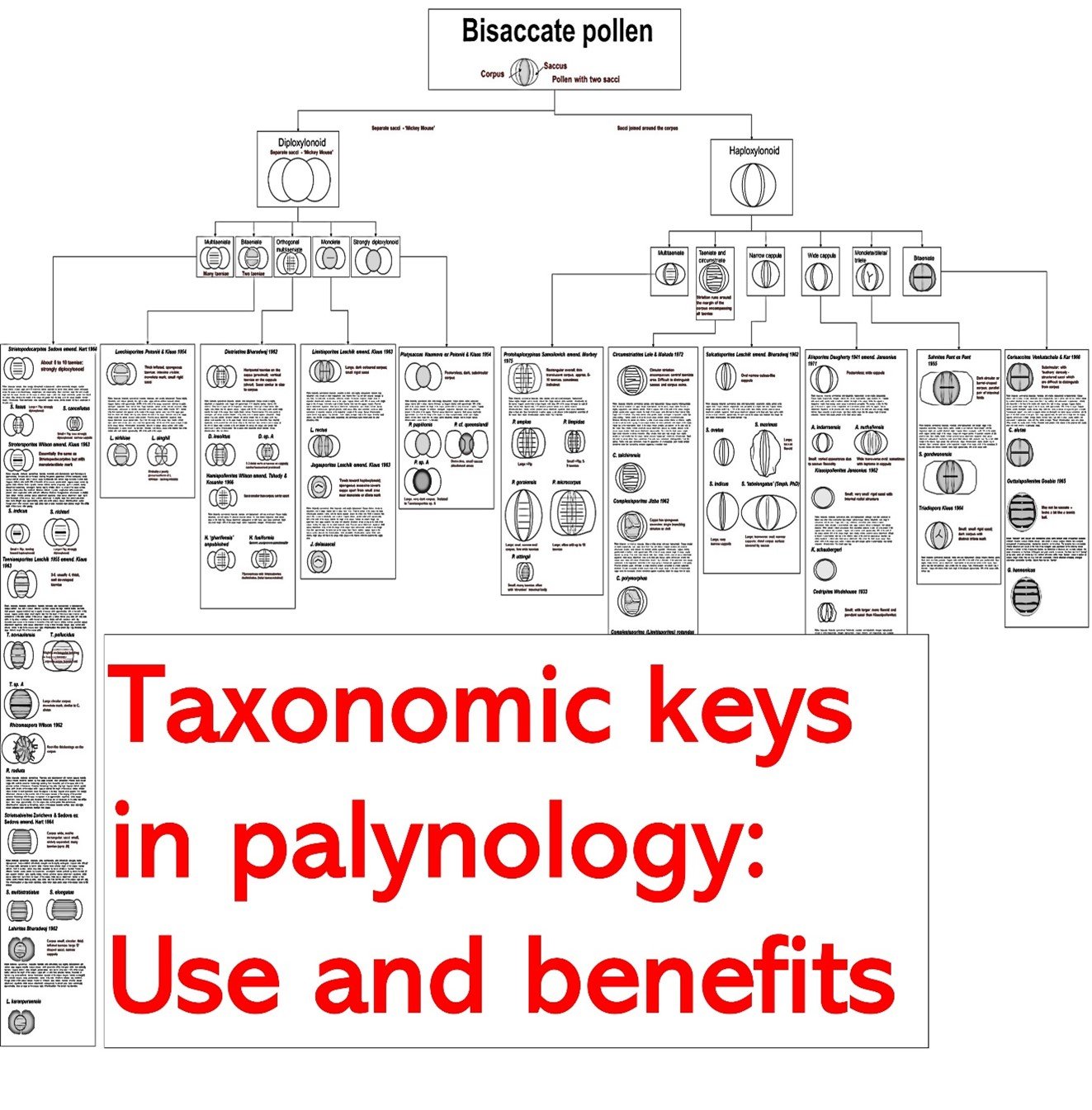

Taxonomic keys

Taxonomic keys – to help in the identification of species – are a vital tool for palaeontologists and palynologists learning their trade, or for experienced palaeontologists starting in a new area. While they can’t replace the academic expert, they can imitate the expert’s thinking processes and decisions. They can also be useful for students and for standardising practical taxonomy in environments where lots of palynologists work together, for example in companies.

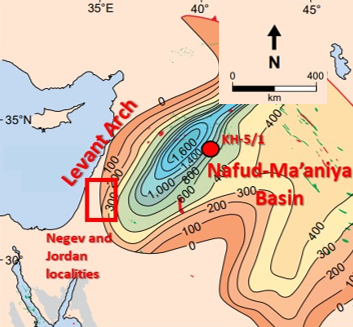

Levant Arch and the Palaeozoic of Arabia

The Levant Arch is a pervasive structural high that runs on a north-northeast trend from eastern Egypt to Turkey, through the Levant. Its existence prompted the use of the term ‘Hercynian Orogeny’ by Gvirtzman & Weissbrod (1984) for the first time in the Middle East, and following this, the widespread use of the term ‘Hercynian unconformity’ across the Arabian Plate. This short article, part of a larger project on the Hercynian unconformity across the Arabian Plate, traces the palynology of the Hercynian unconformity from where the Levant Arch creates a very incomplete Palaeozoic succession to where the Palaeozoic succession is near continuous and without break in the thickest part of the Nafud-Ma’aniya Basin.

Permian palynology since 2007

I was commissioned by the Subcommission on Permian Stratigraphy (SPS) to write a review of advances in Permian palynology since 2007 for the SPS publication Permophiles. The review was published in Permophiles, 2023, volume 75, p. 22-26 (https://permian.stratigraphy.org/files/permophiles/Permophiles%2075.pdf). But the review is published here also.

Update: Reducing CO2 reservoir uncertainty with palynology

Capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) from industrial and power sources and storing it in sub-surface geological formations is an option for reducing emissions into the atmosphere. Palynology (the study of fossil spores and pollen that are common in argillaceous rocks) may have use in the crucial area of the uncertainty caused by geological heterogeneity, specifically the size and arrangement of mudstone baffles to fluid flow. Its use shows how science developed to understand oil and gas extraction can be re-invented to help in the injection and underground management of CO2. Recent work in 2022 and 2023 on Jordanian Permian fluvial clastic sequences has shown how different types of mudstone baffles can be identified by their palynological assemblages. Statistical analysis of palynological assemblages may help in providing an objective, quantitative measure of baffle type and size in the future.

Improved UK Zechstein palynology

The UK Zechstein (Lopingian, Upper Permian) is a thick pile of carbonate/evaporite sediments that accumulated over a period of several million years. In the past rather sparse palynology and palaeobotanical data hinted at minimal evolutionary change over this period suggesting that palynological subdivision (biozonation) would be difficult. New work on the extraction of palynomorphs directly from UK Zechstein salt, rather than from argillaceous sediments associated with salt - and new data from individual mudstone units like those in Cadeby Quarry suggest that there is potential for more and better palynology in the UK Zechstein. This would support the succession’s increased importance in decarbonisation technologies such as subsurface hydrogen storage.

Tackling species variation

In palynology, one of the ways to correlate distant sections in different palaeophytogeographic provinces is to use ‘bridge’ taxa – the few taxa which appear to be common to the provinces, despite their other differences. Bridge taxa become very important when there are no other ways to correlate, for example in non-marine sequences with no other fossils, or in sequences that have no dateable ash horizons. The problem is that bridge taxa may not be well described, or that conceptions of them in different palaeophytogeographic provinces may be different where different ‘schools’ of palynology have grown up. Traditional and formal (‘legal’) documentation in scientific journals with a description, diagnosis and types can help us understand taxa, but not their full variability, their ‘taxonomic distance’ from their nearest neighbours or the way that they ‘grade’ into their taxonomic neighbours. We should use the internet more to create galleries of images of key bridge taxa and not be constrained by journal page and plate limits.

Palynology and carbon

Palynologists have been using δ13C of organic matter and palynomorphs (δ13Corg) - as opposed to δ13C from carbonates (δ13Ccarb) - for several decades. I’ve used it quite a lot in academic and commercial contexts for paleoenvironmental reconstruction and correlation. Here’s my non-exhaustive summary of the uses and pitfalls of δ13Corg in palynology.

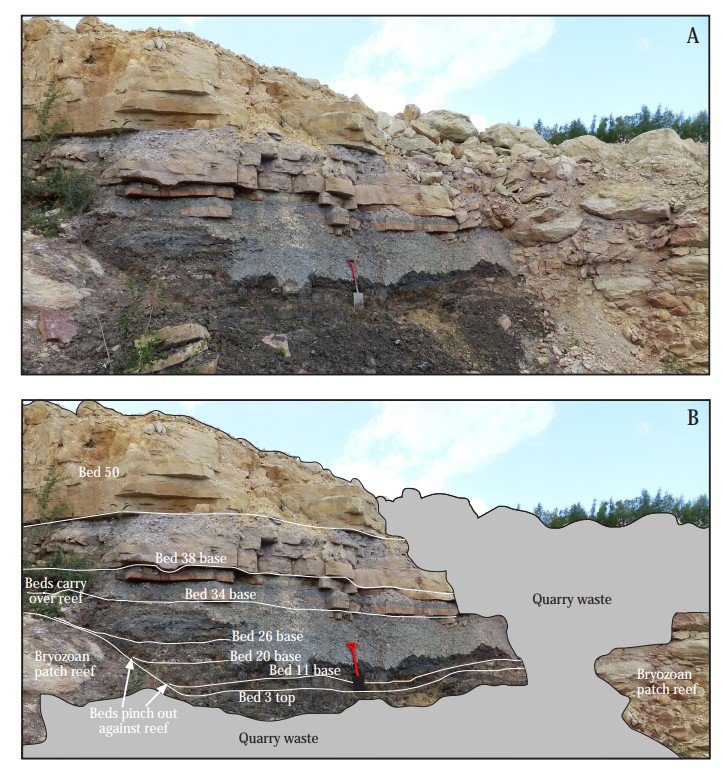

Visualising the buried succession

Palynological and lithological correlation has shown how similar the Carboniferous-Permian glaciogenic and post-glaciogenic rocks of Oman and the Arabian Peninsula are to those of Pakistan. Perhaps this is not surprising given their proximity in plate reconstructions for the time. However the excellent exposure of rocks in the Salt and Khisor ranges allow these succession to be ‘eyeballed’ in a way not possible in Oman and the Arabian Peninsula, allowing largescale 2D and 3D appreciation of the complexities of Middle Eastern Carboniferous-Permian glaciogenic and post-glaciogenic rocks.

Calibrating palynostratigraphy

Palynology is a key tool to correlate subsurface formations, especially where sub-anhydrite seismic is poor and where there is extreme lithological variation between wells. But palynological zonations are often difficult to relate to the subdivisions of global stratigraphy, hampering their value. In this article I show three ways that these connections can be made, and that palynological zonations can be calibrated.

Geo-energy test sites

Our paper published this week shows how important pilot and demonstration projects (PDPs) are to the success of subsurface energy technologies, for example CCS, BECCS, direct air capture and storage (DACCS), aquifer thermal energy storage (ATES), compressed air energy storage, (CAES), and decarbonising heat through district heat networks (geothermal heat, thermal storage). Although these and other technologies have been studied by geologists at laboratory scale and in models and simulations, they require testing at pilot and demonstration scale and in representative conditions not reproducible in labs and models.

Palynology in action: faults

Palynology is usually associated with simple dating or palaeoenvironmental and climate studies, but it can be used to solve larger regional geological problems. One example relates to the origin and history of the Dead Sea Fault famous for its destruction of Jericho. The Dead Sea Fault extends for around 1,000 km, and produced more than 100 km of displacement between the Negev and Jordan. Although the fault in its present form is Miocene in age, an older pre-existing deformed zone was also probably present. Here palynology analysis shows that a precursor to the fault was probably active during the Permian.